This post is the second in a series about including diverse voices in English curriculum while exploring issues and needs related to gifted students. This series will focus on various essays found in the YA nonfiction anthology, Our Stories, Our Voices: 21 YA Authors Get Real About Injustice, Empowerment, and Growing Up Female in America.

View the first post and more about this anthology here. Guidelines for integrating this text or individual essays in your curriculum and how to set up things appropriately and effectively with your students are also included at this first post.

How do you include and explore diverse nonfiction related to LGBTIQ+A issues in your English classroom?

Share with us below!

What Am I “Supposed” to Be?

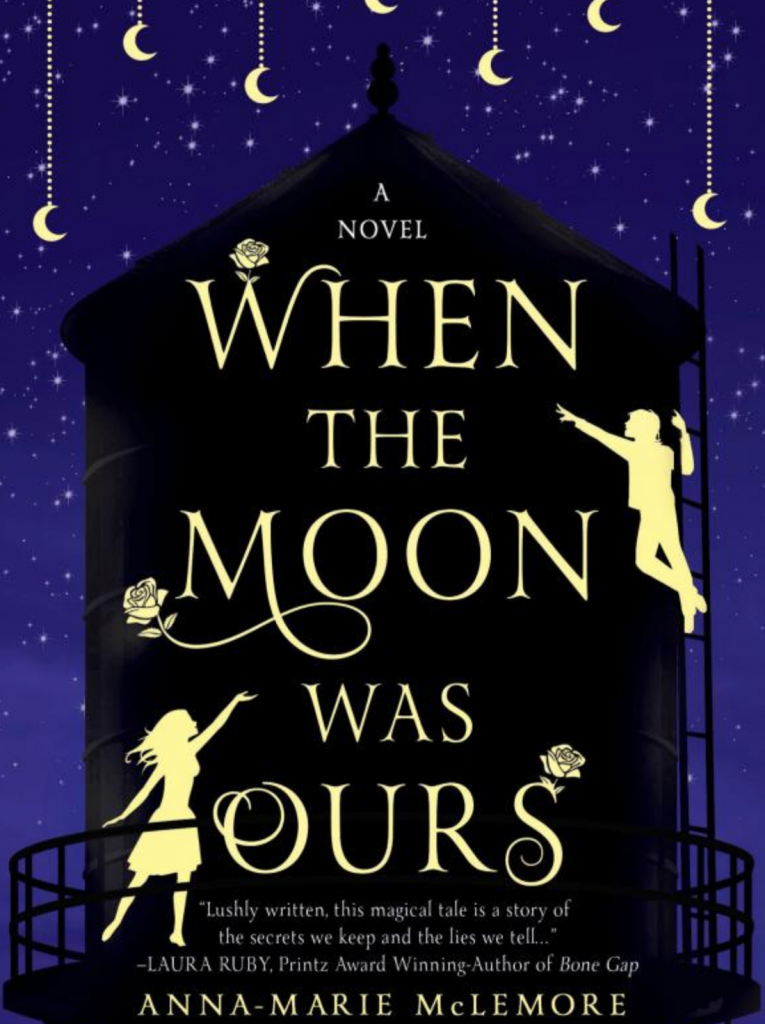

YA author Anna-Marie McLemore (The Weight of Feathers, When the Moon Was Ours, Wild Beauty, and Blanca & Roja) offers an essay, “Her Hair Was Not of Gold,” that raises questions about how we define gender identity, sexual identity, and religious identity. (Since the first posting, McLemore has shared their non-binary identity and the preference for they/them/theirs pronouns. Note that the essay was also written before this time.) In this essay, they share how growing up they felt excluded by their religious denomination and the sexual and gender categories that others required, saying, “it took “a long time to accept myself as the queer Latina girl I was.” This essay is a rich mine to explore with your students and can partner well with a variety of readings in your curriculum.

Before You Begin

Because each of these stories share voices that are often silenced, they must be given “big space” in the classroom. By that we mean stories must be read more than once, and annotated–listened to, carefully. These stories should be celebrated. They should invite a reader to go inward. They should invite a conversation between the reader and the writer.

These suggested writing and discussion prompts assume that you have done work to set up a safe space in your classroom, that you offer opportunities for students to journal privately as well as for you as the audience, and that you remind students of how to engage respectfully when sharing different opinions. Some questions below are best saved for independent writing, while some might work for small-group discussion, and others, for large-group discussion.

These questions assume that students will have a choice of a few questions and from more than one section, and that they can also propose their own prompts in response. Students should be encouraged to make a personal and emotional connection as well as an intellectual connection with McLemore’s story.

These are not stories that should be used as a preface to engage in debates over issues or politics, nor should they be assigned as essays to pick apart for those political points. These are stories that should encourage thoughtful reflection rather than argument.

Work with your school counselors, department chairs, and administrators as necessary to ensure you can appropriately support students who may come forward with difficult circumstances or stories.

In some circles, English teachers wonder whether empathy can be taught. Can a student who’s never experienced McLemore’s particular circumstances possibly empathize with them? Not fully. But students who don’t know won’t know any more unless we ask them to connect. A student learning that such events happen to other people should be able to find points of connection and attempt to learn more.

Questions for Writing and Discussion of “Her Hair Was Not of Gold”

Making a personal connection

- McLemore is laughed at by a teacher for wanting to perform the role of the Virgin Mary, and it marks them for life. Review their experience, then think of a time when an adult or someone in a position of authority said or did something that marked you. If you can, tell that story and how you see yourself now.

- Find a few sentences that capture how McLemore responded to being told how to be a girl, about who to love, and about how to be religious. What surprises, impresses, or strikes you about her particular response?

- Have you ever been told that you did not fit the definitions of gender, sexuality, or religious appearance or belief? How did you respond?

- McLemore begins the essay by describing how “she” (her identity at the time) is “not of” the standard definitions of beauty and sacredness (gold, AKA blonde, and other physical features). In what ways does she redefine herself by the end of the essay?

- How does McLemore define God? Do you define God or spiritual expression in a certain way? Talk about your feelings in responding to their definition. For example:

- McLemore declares that “no one else, not teachers, not painters, not the world–gets to draw the boundaries of where God’s light reaches” (McLemore 17). What does McLemore mean by “God’s light”?

- McLemore also talks about their teen love, a transgender boy, being a “child of God” (14). What do you think that phrase means to them? Does “child of God” mean something to you personally, and if yes, how do you define it?

- How has someone you know been treated differently when it comes to gender, sexuality, or religion? What has been your role when interacting with this person? Why? Would you do anything differently when you next interact with this person?

- McLemore shares how “the pull toward the kind of churches I once knew has never quite left me. Even knowing they wouldn’t accept me or my husband, I still feel it.” Have you ever been pulled back to people or places who have rejected you, even though you don’t feel welcome? Why do you think you felt and/or followed that pull?

- How are you defining boundaries of what it means to be a certain gender, sex, or religion? Explain with a story.

- Write a scene from your life where you were helped, encouraged, or uplifted when it comes to gender, sexuality, or religion.

Get curious

- Knowing that McLemore is non-binary and has revisited their gender identity, what questions do you have about gender identity in your own life? How is their journey sparking questions for you?

- McLemore dove into research to learn more about the historical Jesus. What types of research do you enjoy pursuing, and how has it expanded your world view? How might what you are learning help others?

- McLemore’s teen love shares this epiphany:

“Weird, isn’t it?” he asked, still watching the sunset, taking a swallow from the bottle and then handing it to me. “We see all those paintings and we take it as some kind of fact that he was white even though it makes no sense.”

(15)

- McLemore notices how Mary and Jesus are often portrayed as blonds. Have you ever investigated an image that appeared to be the standard image for everyone because you were curious about its origins? What did you find out?

- Note in the above question that the masculine gender was the default adjective (“blond” versus “blonde“). Research masculine and feminine spellings for any language you might speak and pose some questions about the history and etymology of gender as it applies to language. What discoveries do you make?

- What did you learn from McLemore’s experience with being rejected and how they overcame that experience? What more would you like to know?

- What are two questions you have for McLemore based on their essay? Where do you want to grow in your understanding of other people’s lives? What questions do you wish people would ask you about your life experience?

Make connections

- What stories, poetry, essays, and other art (films, paintings) have we experienced this year that connect to McLemore’s experiences? How do they connect?

- McLemore is a young adult author. Check out their novels and decide whether you might try one. What about her work might be important to help you grow as a reader, a thinker, and as an individual?

- If you have another idea for a post in response to this essay, propose it to the teacher.

Be Ready to Support Students

No matter what your background, you can support students as they write their way through new understandings or tell you stories you’ve never heard. Be open to their experiences and listen hard. Seek support from your school counselors should you see any writing that speaks to student trauma or pain, so you can respond sensitively. The most important thing we can communicate when reaching out to our students is letting them know they are seen and heard, and they are not alone.

Find Partner Texts

Works you might consider teaching in tandem with this essay include

- The Miseducation of Cameron Post by Emily M. Danforth

- Gabi, a Girl in Pieces by Isabel Quintero

- Hold Still by Nina LaCour

- Every Day by David Levithan

- Openly Straight by Bill Konigsberg

- Simon vs. the Homo Sapiens Agenda by Becky Albertalli

- I’ll Give You the Sun by Jandy Nelson

- Will Grayson, Will Grayson by John Green and David Levithan

- None of the Above by I. W. Gregorio

- If You Could Be Mine by Sara Farizan

Remember the Spirit

As you navigate this anthology with students and think about how to set up fruitful reflection and discussion, remember these words from Reed:

This is our love letter to America, to the young people who are hurting and scared. You are not alone. We hear you. We are listening. We stand by you. We will survive as we have always survived: together.”

(xii)

Let’s make the classroom space a community where all gifted students can raise their heads and show their rainbows without doubt or fear.

Stay tuned for future posts on this anthology and how to include it in your classroom.

Leave a Reply